note: this text was submitted as an assignment for Contemporary Art and The Global module at SOAS, University of London, and was not intended as a real exhibition proposal in the foreseeable future.

when I submitted this assignment, it was more than just an attempt to get a good grade—it was an excerpt of an existential identity crisis and a 'love letter' to my hometown. Eventually, this piece received quite positive feedback from my convenor.

Curatorial Proposal: Recasting Shadows

Recasting Shadows is an exhibition that reexamines how Indonesians perceive their identities, shifting from a narrative rooted in colonial victimhood to one that embraces complexity, autonomy, and a multifaceted identity. Through paintings, sculptures, and installations, this exhibition explores Indonesia’s journey from the shadows of colonial histories to the light of self-realization and nuanced self-determination (Hujatnikajennong, 2010).

Drawing inspiration from Plato’s allegory of the cave, Recasting Shadows reflects on the collective journey of Indonesians moving from external narratives and imposed perceptions to a vibrant complexity of modern identity. Much like the prisoners in Plato’s cave mistaking shadows for reality, Indonesians have grappled with an identity shaped by colonial and feudal frameworks (Vickers, 2020). This exhibition illuminates the transformation from these shadows—including reductive archetypes and victimhood narratives—to a dynamic, self-determined understanding of identity.

Indonesia, an archipelago with a long history of trade, colonial rule, and socio-political upheavals, has continuously evolved amidst external influences and internal struggles. From early colonial encounters with European powers to the nationalist fervor of the mid-20th century and the socio-political turbulence of the Suharto regime, the country's historical narratives often emphasized victimhood. However, contemporary Indonesian artists are reclaiming and redefining these narratives, presenting layered interpretations of their identity (Supangkat, 1993).

The evolution of Indonesian modern art reflects a synthesis of traditional aesthetics and contemporary paradigms, where artists negotiate between local identities and global influences. Modernism in Indonesia emerged not as a mere adoption of Western styles but as a process of reinterpretation, creating a nuanced dialogue between the past and present. Recasting Shadows thus becomes a lens to view Javanese cultural and societal evolution through the eyes of its own people.

Javanese art and culture has traditionally been framed through a mystical and static lens, shaped by colonial perspectives that emphasized monarchical aesthetics. This static view has been consistently challenged by critics and artists who seek to emphasize the fluidity and adaptability of Javanese identity. By redefining tradition as a dynamic process, they underscore how contemporary Javanese art embraces innovation while remaining grounded in cultural memory (Yuliman, 1976).

The exhibition title, Recasting Shadows, draws on the metaphor of wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) as a symbol of Javanese tradition. Here, shadows become a dynamic force—reshaped and reinterpreted by artists who navigate contemporary frameworks. The selected artworks highlight the fluidity of identity and tradition, illustrating how cultural symbols evolve within changing socio-political contexts.

Banyumas, geographically positioned between the ancient kingdoms of Mataram and Pajajaran, embodies a distinct cultural ethos. Known for its phrase, "adoh ratu, cedhak watu" (far from the king, close to the stone), Banyumas has historically resisted the feudal structures of Javanese kraton (palace). This spirit of independence persisted through various historical upheavals, including the communist uprising of 1965, leaving deep cultural and political scars.

By spotlighting artists born in Banyumas area (including Cilacap and Purbalingga), the exhibition situates their works within this rich, complex history. Artists such as Sunaryo, Ugo Untoro, Nasirun, Bandu Darmawan, and Munir Al Sachroni defy centralized narratives of Javanese culture, rejecting colonial and feudal gazes. Instead, their works unconsciously draw from Banyumas’ ethos of resilience and humor, asserting autonomy and complexity in their artistic practices.

Inspired by the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (Indonesian New Art Movement) of the 1970s, Recasting Shadows highlights works that dismantle hierarchies and critique the elitism of “high art.” The New Art Movement emphasized pluralism and socio-political critique, rejecting the dominance of decorative styles. This ethos resonates deeply with the featured artists, whose works navigate local and individual expressions while challenging broader narratives.

Recasting Shadows aspires to be more than an exhibition; it seeks to ignite a dialogue about shifting identities, where Indonesians move from narratives of victimhood to narratives of empowerment. By showcasing artistic responses to Indonesia’s layered histories, the exhibition invites audiences to reflect on the intricate, self-determined nature of modern Indonesian identity in the contemporary era.

The featured artists in this exhibition collectively navigate the intricate relationship between tradition, modernity, and identity, creating a multifaceted dialogue within Indonesian contemporary art. At the heart of these explorations lies the interplay of light, shadow, and materiality, serving as a metaphor for introspection and transformation. Sunaryo’s installation, Lawangkala (The Door of Time), invites viewers into a liminal space, blending natural materials and controlled lighting to evoke cycles of entrapment and release. Shadows cast by the structure become dynamic agents of meaning, aligning closely with themes of personal and collective reflection.

Similarly, Nasirun’s Gunungan Emas deconstructs the classical gunungan motif, transforming it into a critique of societal imbalance. By layering sacred and profane imagery, Nasirun interrogates how cultural symbols are repurposed in contemporary contexts, challenging viewers to reconsider the roles of tradition in a globalized world. This tension between the sacred and the commodified resonates with Ugo Untoro’s Btara Guru on a Missile, where mythology meets geopolitics. The sculpture’s juxtaposition of a Javanese deity atop a missile critiques humanity’s ethical failures, emphasizing the fragile balance between power and harmony.

The exploration of shadows continues in Bandu Darmawan’s Pernyataan Tidak Tertulis (Unwritten Statement), an interactive installation that uses silhouettes and everyday objects to create participatory narratives. Drawing inspiration from wayang kulit, Bandu transforms the audience into active participants, blurring the boundaries between performer and observer while confronting unspoken elements of human connection. Meanwhile, Munir Al Sachroni’s Tidak Pernah Kering (Never Dry) channels the urgency of resistance, critiquing socio-political exploitation through jagged, frenetic compositions that elevate marginalized voices and collective memory.

Together, these works illuminate a shared commitment to redefining identity, asserting complexity, and fostering transformation within the evolving landscape of Indonesian art. Through their varied approaches, the artists challenge dominant narratives while celebrating the interplay of tradition and innovation.

Proposed Venue is The Indonesian National Gallery, Jakarta. This venue holds historical significance as a legacy of colonial architecture, which has evolved to witness and host the progression of Indonesian art. It symbolizes the transformation from colonial impositions to a space that celebrates the autonomy and diversity of Indonesian cultural expression.

A robust public program will complement the exhibition. Panel discussions featuring art historians, curators, and participating artists will explore key themes and provoke dialogue, encouraging deeper audience interaction with the exhibition's narratives. Workshops will provide hands-on opportunities to engage with techniques that explore the interplay of light and shadow, drawing inspiration from traditional wayang kulit and contemporary digital art practices. Guided tours, led by curators and docents, will offer layered interpretations of the artworks, enriching the visitor experience by connecting each piece to the exhibition's broader themes.

References

Hujatnikajennong, A. (2010). The Contemporary Turns: About the Indonesian Art World and the Aftermath of "the 80s".

Supangkat, J. (1993). Seni Rupa Era 80. Jakarta Art Council.

Vickers, A. (2020). The Impossibility of Art History in Indonesia. AESCIART Conference Proceedings.

Yuliman, S. (1976). Seni Lukis Indonesia Baru: Sebuah Pengantar.

Lawangkala (The Door of Time)

Artist: Sunaryo

Year: 2018

Medium: Bamboo and Fiber-Based Materials

Dimensions: Variable

Description:

Lawangkala, derived from the Javanese words lawang (door) and kala (time), is a transformative installation by Sunaryo, inviting viewers to step into a liminal space where time, memory, and the self converge. Originally conceived in 2018 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Selasar Sunaryo Art Space, the tunnel-like structure made of bamboo and fiber-based materials resembles a traditional fish trap (bubu), signifying cycles of entrapment and release.

Visitors walking through Lawangkala are metaphorically and physically immersed in an act of passage—entering through the "door of time" to confront the transient nature of existence. This journey aligns seamlessly with the thematic essence of Recasting the Shadows, where the installation becomes a site of transformation. Shadows, cast by the woven structure under controlled lighting, play with perception, creating a dynamic interplay of light and darkness that speaks to the dualities of life—presence and absence, clarity and obscurity.

In a semiotic reading, Lawangkala acts as a threshold symbolizing change. The tunnel shapes an introspective experience, urging participants to reflect on their place within the continuum of time. Shadows along the passage evoke the fleeting traces we leave behind, a reminder of impermanence yet also of renewal. Walking through Lawangkala becomes a ritual of shedding old narratives and embracing new possibilities, embodying the exhibition's exploration of transformation and the metaphoric power of shadows.

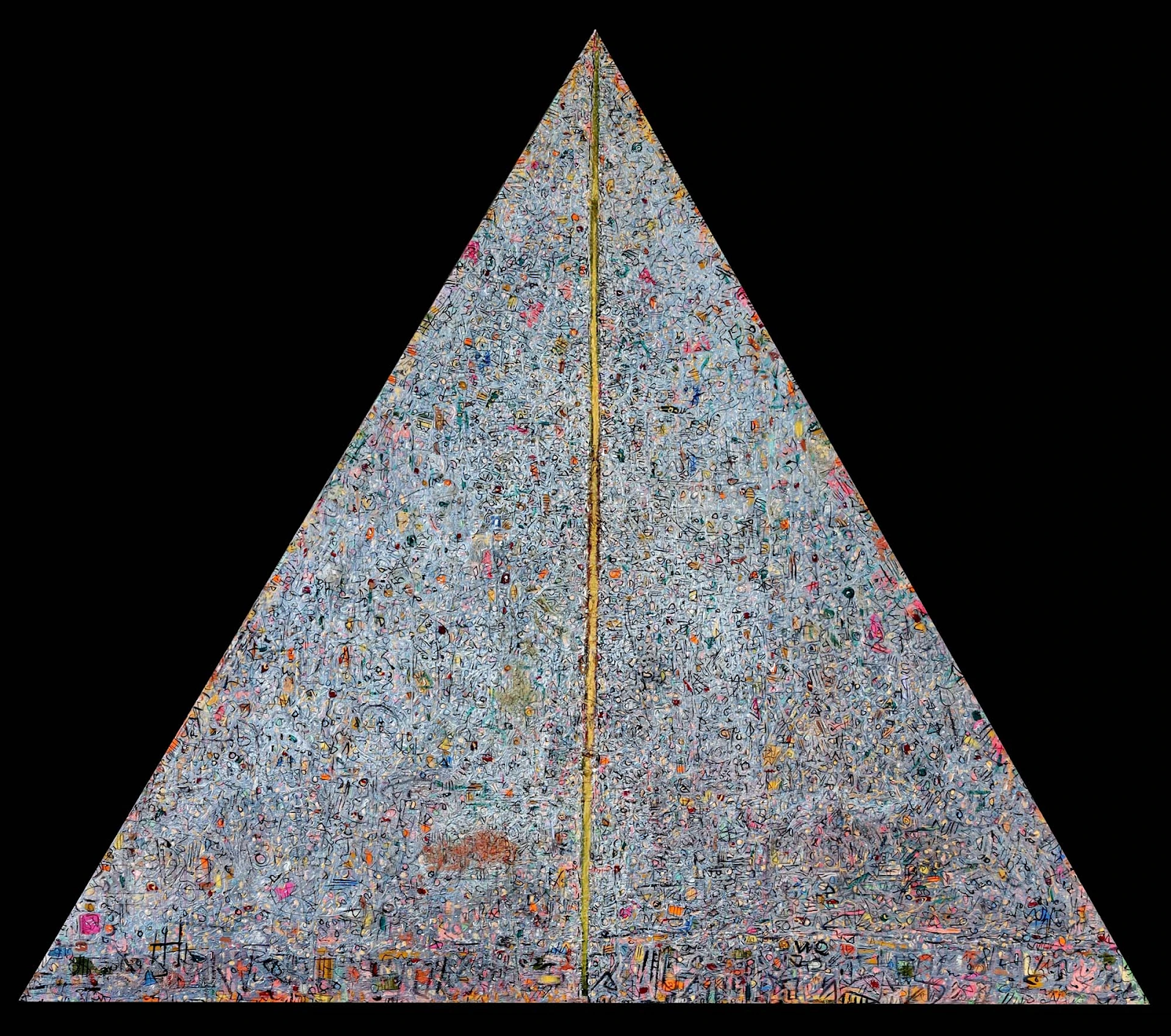

Gunungan Emas

Artist: Nasirun

Year: 2018

Material: Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: Triangular, 182 x 210 cm

Description:

Nasirun’s Gunungan Emas transforms the classical gunungan motif from Javanese wayang into a postmodern critique of contemporary society. Traditionally symbolizing cosmic balance and transitions in wayang performances, the gunungan is reimagined to highlight societal dissonance and the commodification of spiritual values.

The triangular canvas, dense with layered imagery, mirrors the complexity of modern life, where sacred ideals clash with profane pursuits. The golden vertical axis evokes the sacred mountain (axis mundi), yet its fractured appearance reflects the erosion of harmony in a consumer-driven era. Nasirun critiques how traditions are repurposed, often at the expense of their original meaning, within a globalized context.

Gunungan Emas challenges the viewer to reconsider the role of cultural symbols in a world grappling with inequality and environmental degradation. By deconstructing the gunungan into a chaotic mosaic, Nasirun shifts its meaning from a static emblem of unity to a contested site of transformation. The golden axis underscores this tension, suggesting that while spiritual ideals endure, they are frequently overshadowed by greed and ambition. This work situates itself at the intersection of heritage and modernity, inviting reflection on the ways traditions are reshaped in response to global forces.

Btara Guru on a Missile

Artist: Ugo Untoro

Year: 2023

Material: Andesite Stone from Merapi mountain

Dimensions: Variable

Description:

Ugo Untoro’s Btara Guru on a Missile provocatively merges mythology with modern geopolitics. In this sculpture, Btara Guru, a Javanese deity associated with cosmic wisdom, trades his traditional mount, Lembu Andini, for a missile. The piece critiques humanity’s disconnection from nature and the escalating tensions of global power struggles.

Carved from volcanic stone sourced from Mount Merapi, the work reflects Ugo’s admiration for stone’s durability as a medium to communicate timeless messages. Part of the The Archeology Story series, this sculpture examines themes of environmental degradation, shifting ideologies, and the ethical challenges of technological advancement. The juxtaposition of sacred iconography and military weaponry underscores the fragile balance of peace, exploring how modern pursuits often undermine traditional values.

The missile symbolizes power and control but also questions humanity’s relentless focus on dominance. Ugo’s piece warns that change, though inevitable, can erode harmony and natural connections. The work uses satire and critique to highlight the double-edged nature of progress, prompting viewers to reflect on how nations can assert themselves with dignity and autonomy in an unstable world.

Pernyataan Tidak Tertulis (Unwritten Statement)Artist: Bandu Darmawan

Year: 2018

Medium: Interactive Installation with Light, Shadow, and Found Objects

Dimensions: Variable

Description:

Bandu Darmawan’s Pernyataan Tidak Tertulis explores the ephemeral power of light and shadow to convey unspoken narratives. Using simple materials like a light projector and everyday objects, the installation transforms viewers’ physical presence into poetic, shifting silhouettes. Shadows on a blank canvas blur distinctions between the performer and the audience, creating a participatory space where meaning emerges through interaction.

This work draws from both traditional and contemporary visual vocabularies, resonating with the storytelling heritage of wayang shadow puppetry. By employing shadows as dynamic agents of meaning, Bandu critiques the transient, often overlooked elements of human connection. The installation captures fleeting gestures and narratives, encouraging participants to confront their "unwritten statements" and the silences within communication.

As part of Recasting Shadows, the work exemplifies the exhibition's focus on reimagining shadows as metaphors for liminality, ambiguity, and transformation. It challenges traditional notions of materiality, emphasizing the impermanence of presence in an increasingly mediated world. By anchoring shadows in real-time and space, Bandu’s installation prompts reflection on identity, absence, and the ways we navigate the boundaries between physicality and representation.

Tidak Pernah Kering (Never Dry)

Artist: Munir Al Sachroni

Year: 2021

Material: Wood on wood

Dimensions: 203.2 x 254 x 12.7 cm

Description:

Munir Al Sachroni’s Tidak Pernah Kering (Never Dry) is a visceral depiction of resistance, trauma, and critique deeply rooted in Indonesia’s socio-political struggles. The painting’s chaotic composition, with its vivid, frenetic strokes and haunting imagery, reflects the enduring violence and exploitation of land, people, and justice. This work draws upon Munir’s upbringing in Banyumas, Central Java, and his advocacy against land grabs and environmental destruction perpetuated by state and corporate forces.

The jagged forms and distorted faces evoke a sense of anguish, while textual elements and symbolic references weave together narratives of oppression and defiance. A central motif of a crucified figure looms above, resonating with themes of martyrdom and systemic violence. The vibrant yet unsettling palette underscores the tension between beauty and brutality, a hallmark of Munir’s Art Brut-inspired practice.

Part of a broader practice involving performance and visual art, Tidak Pernah Kering critiques power structures while elevating the voices of marginalized communities. Munir channels the energy of protest, merging personal and collective memory to create a work that is both intimate and universal. It speaks to the persistence of resistance, the scars left by exploitation, and the hope for justice and renewal in Indonesia’s future.

My convenor's comment:

"A very compelling and thorough proposal which clearly and eloquently presents the rationale, context and artist selections. There is plenty of contextual detail here but along with the concept of the shadow and the focus on contemporary artists from Banyumas you provide a coherent project.

The wall labels are concise and informative and offer multiple entry point to each work. Reference to the proposed exhibition venue The Indonesian National Gallery is also measured and reasoned. A diligent and impressive curatorial proposal."